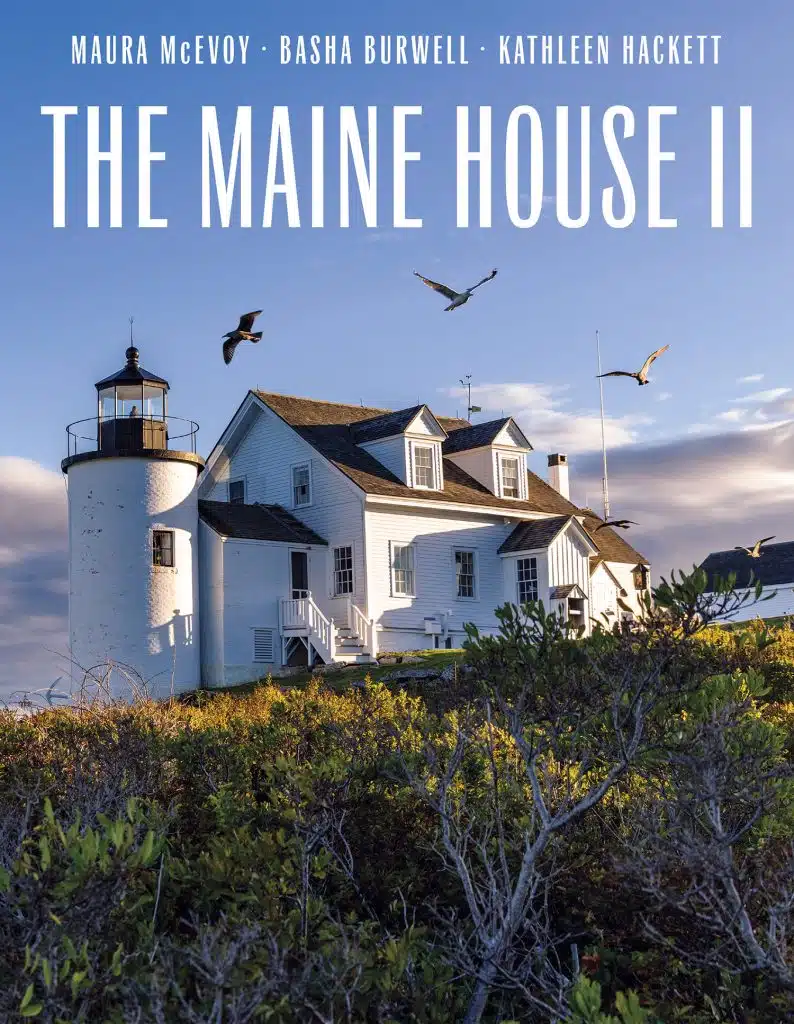

Scenes from “The Maine House II”: Inshore, Inland, and Island Cottages

Rich in photos and feeling, “The Maine House II” shows how the buildings we inhabit can be a beautiful expression of where we live.

A boat shed turned summer cottage near Acadia National Park.

Photo Credit: Maura McEvoySometimes people belong to a place so deeply, they can’t imagine being anywhere else. Maybe it’s land where generations of their ancestors put down roots, or maybe it’s somewhere they’ve spent their whole lives searching for—either way, explaining exactly what that place means to them can prove elusive.

A few years ago, three women who shared a deep love of Maine and boundless creativity set out to show in words and photographs how the homes we choose not only reflect who we are, but also tell the story of a place that, to us, is unlike any other. Maura McEvoy, Basha Burwell, and Kathleen Hackett traveled the state’s back roads and waterways to produce The Maine House, which they said was inspired by “our desire to record the Maine of our childhoods, a Maine that is swiftly vanishing.” Offering an intimacy not unlike that of looking through the family album of someone you have just met, the book struck a chord with readers around the world.

This year, its sequel, The Maine House II (Vendome 2024), continues the trio’s quest. They drove thousands of miles, rowed or were ferried by fishermen, knocked on countless doors, and made new friends, all in pursuit of the question: What makes a house a Maine house? And beyond that, they wanted to show the indefinable qualities that—to paraphrase Burwell describing her own cottage—make a home our ballast, anchor, and compass.

In putting together their sequel to The Maine House, the authors looked for properties that have been preserved, restored, and sensitively expanded to show how vital it is “to rescue Maine’s quirky architectural history if we are going to preserve its singular nature, one that goes hand in hand with reverence for the land.” Fittingly, the home profiles are arranged by what type of land they occupy: inshore, inland, and island.

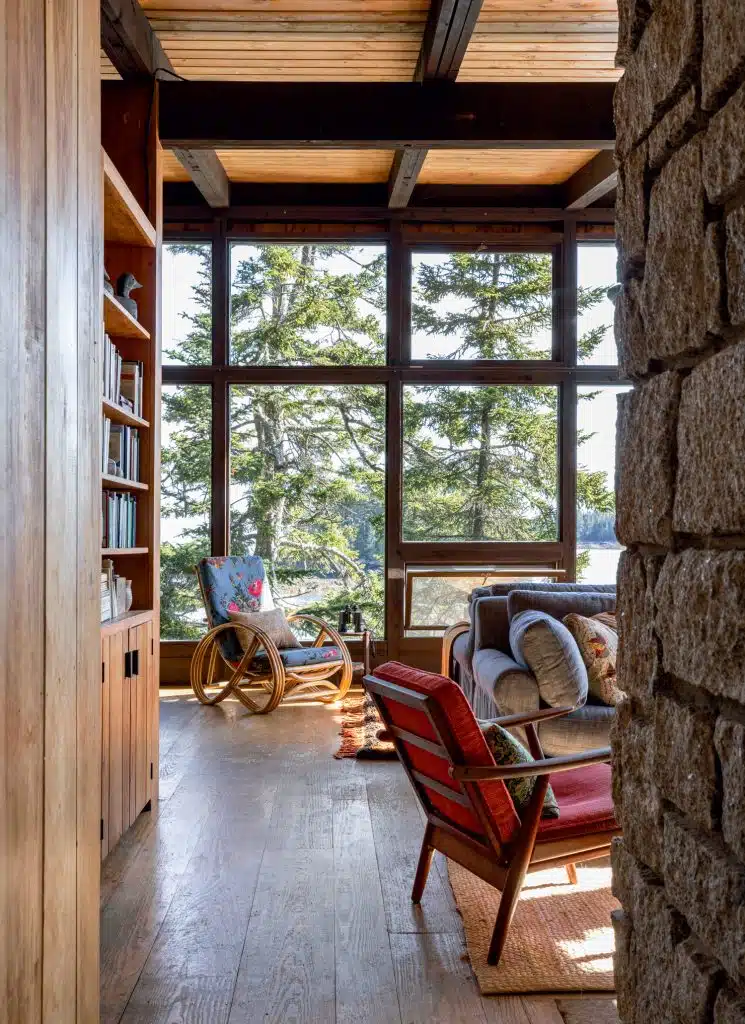

Inshore: The Falls at Crockett Cove

Nestled into evergreens on the rocky shore of Maine’s Deer Isle, the Falls at Crockett Cove is among a handful of cottages that survive from the nearly 50 that were designed or renovated in this area by Emily Muir, a self-taught architect and modernist pioneer. Built in 1968, the property has been restored and updated, but current owners Carolyn and Ray Evans have taken pains to honor Muir’s vision: painting cabinets in original colors, matching new flooring to the old. “What was important to her is now important to me,” Carolyn tells the authors.

Inland: Panther Pond

The Maine tradition of rustic family cabins known as summer camps lives on at Panther Pond, a birch-accented structure that reposes on its namesake lake in the state’s southern interior. It was built in 1907 by Robert Treat Whitehouse, whose wife, Florence Brooks Whitehouse, was a noted author, artist, and suffragist. Florence’s great-granddaughter, Anne Gass, is among the group of siblings who are now the property’s caretakers, and when she’s at the camp, Anne often thinks of the women who came before her: folding towels on the bed just as she does now, or turning the kids loose to spend all day in the woods.

And as with previous generations, Anne and her siblings often invite guests here. But whether newcomers are asked back depends on the amount of pioneer spirit they bring to staying in a 117-year-old lodge, where a chipmunk might hop onto your bed. Wildlife is a fact of life here, as is the rough-hewn decor that’s so old that Anne doesn’t even know where it came from. “What she does maintain, however,” the authors write, “is that it will never change.”

Island: The Lighthouse

“There is beauty and dignity in leaving things as they are,” the authors write. “And, perhaps, nowhere is that more compelling than in the lighthouse where Jamie Wyeth lives through all four seasons.” That lighthouse—Tenants Harbor Light, built in 1857 on an island in southwestern Penobscot Bay—was bought in 1978 by Jamie’s father, famed artist Andrew Wyeth, himself the son of another art legend, N.C. Wyeth. Jamie carries on the family legacy as a distinguished painter in his own right, although in making this lighthouse his home, he knew he would be living and working in a place that was among his father’s favorite subjects.

“My father pretty much painted it all,” Jamie says, adding jokingly, “I thought maybe I’d paint the bugs.” But instead he found endless inspiration in the island, the water, and especially the gulls that are his constant companions. “I could live four lifetimes and not scratch the surface of what this place offers up to me every day.”